Approximately 45,000 – 38,000 BC, the Cro-Magnon and Neanderthal’s vied for supremacy over the natural domain upon which they roamed. Over time, the Cro-Magnon’s – direct ancestors to modern humans (Homo sapiens) – displaced the Neanderthal tribes whether by natural selection, direct confrontation or disease. Around this time several civilizations spring up within the Mesopotamian region. Then, as modern man continued to spread out from the African plains to the Fertile Crescent along the Euphrates and Tigris river valleys (an area covered by present day Iraq, Syria and Azerbaijan), a dramatic change in ancient society occurred. Civilizations began to experiment in basic food production and with time the favorable topography and climate yielded a bounty of crops. The descendants of these ancient peoples refined the agricultural model of their ancestors by incorporating new crop cycles and domesticating animals. Those tribes that successfully transformed their societies into agrarian based models soon out-produced traditional hunter gatherer societies, resulting in their ability to sustain greater populations. Over time, these larger agriculture based populations grew immune to germs and disease through their exposure to beasts of burden and indigenous plants that they incorporated into their flourishing societies.

Larger populations, of course, required a more sophisticated form of government and a departure from traditional hunter gatherer tasks. As the agrarian societies matured, so did their political systems and their literacy leading to the creation of more specialized roles chiefs, priest, scribes, armies and farmers. The complexities introduced by the new society paradigm forced the agrarian people to find innovative solutions to the mundane and pressing issues of the day, ultimately leading to new technology in the areas of warfare and agriculture. Subsequently, the agrarian societies exerted their relative advantage over the more primitive hunter-gather tribes that still relied on their traditional means for sustenance. Whether through direct conflicts, or via the spread of germs and disease, the agrarian societies eventually conquered the hunter gatherer tribes across Eurasia.

From these origins, the earliest civilizations take root.

Cro-Magnons are recognized as the earliest known race of modern humans, Homo sapiens. Generally considered the earliest European descendants, Cro-Magnons lived between 10,000 and 35,000 years ago. The first Cro-Magnon specimens were discovered in France in 1868 along with many sophisticated tools, artifacts and cave paintings. Cro-Magnons are credited with creating the first calendar nearly 34,000 years ago

Cro-Magnon in the Vezere Valley

During construction for a railroad in 1868, a rock shelter in a limestone cliff was uncovered. Near the back of the shelter, an occupation floor was recognized, and when excavated, it revealed the remains of four adult skeletons, one infant, and some fragmentary bones.

The condition and placement of ornaments, including pieces of shell and animal tooth in what appears to have been pendants or necklaces, led the researchers to think that the skeletons were intentionally buried in a single grave in the shelter.

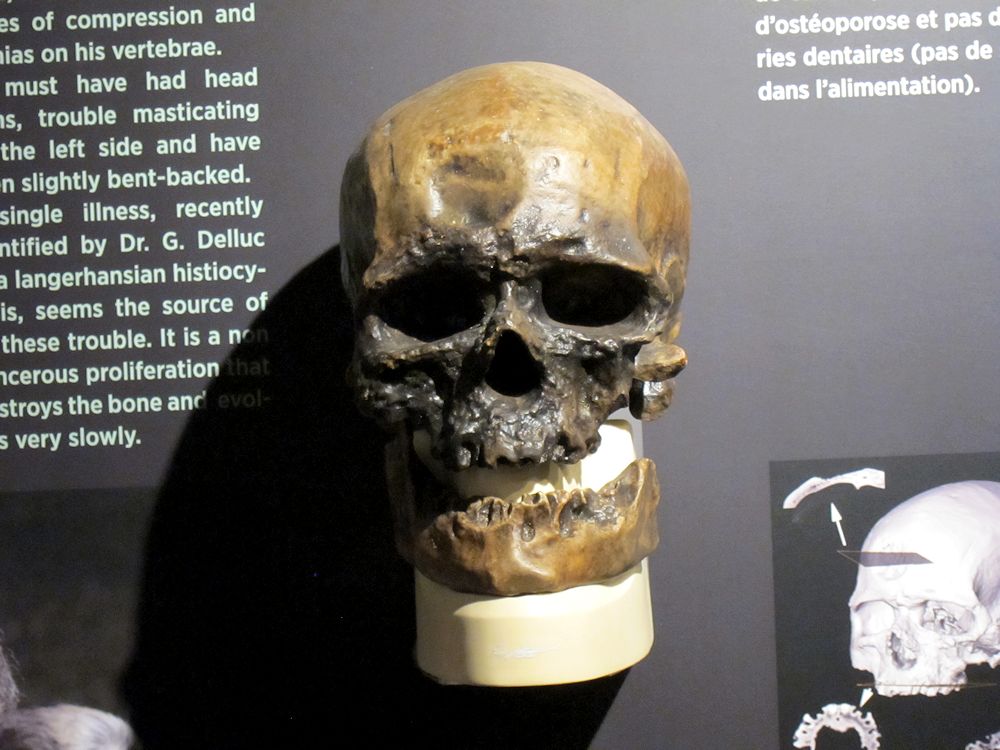

Cro-Magnon preserved the skeleton of an adult male. The individual was probably middle-aged (less than 50 years old) at his death on the basis of the pattern of closure of cranial sutures. The bones in his face are noticeably pitted (see top photograph) from a fungal infection. The skull was complete except for the teeth, which are reconstructed in the cast photographed here.

While the Cro-Magnon remains are representative of the earliest anatomically modern human beings to appear in western Europe, this population was not the earliest anatomically modern humans to evolve.

The skull of Cro-Magnon does, however, show the traits that are unique to modern humans, including the high rounded cranial vault with a near vertical forehead. The orbits are no longer topped by a large browridge. There is no prominent prognathism of the face. Analysis of the pathology of the skeletons found at the Les Eyzies rock shelter indicates that the humans of this time period led a physically tough life.

In addition to the infection noted above, several of the individuals found at the shelter had fused vertebrae in their necks indicating traumatic injury, and the adult female found at the shelter had survived for some time with a skull fracture.

The survival of the individuals with such ailments is indicative of community support of individuals, which allowed them to convalesce. Associated tools and fragments of fossil animal bone date the site to the uppermost Pleistocene, probably between 32,000 and 30,000 years old.