Update 2013

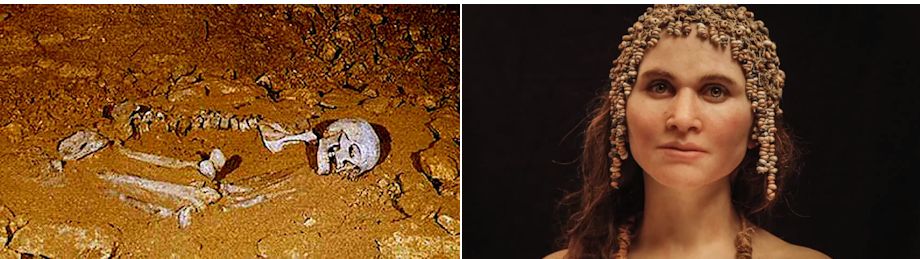

Properly piecing together a rare early human skull (12,000 to 15,000 years old!) is a difficult task, but Robert Martin and JP Brown are pioneering the usage of medical technologies to give us a better picture of what Magdalenian Woman really looked like.

Although previously referred to as “Magdalenian Girl,” Field Museum Curator of Biological Anthropology, Dr. Robert Martin, has established that this specimen was likely an adult woman. Found in a cave in France in 1911, many myths and legends have been built around the story of Magdalenian Woman. One thing we do know for sure is that in 1926, Henry Field purchased the skeleton in New York City, packed it in his suitcase and returned to Chicago on a train. Since then the Field Museum has continued to learn new things about Magdalenian Woman, human culture and the world in which we live.

Tucked away in the Beune Valley a few kilometres from Les Eyzies, the Cap Blanc Prehistoric Centre reveals another aspect of Prehistoric Art Sculpture. Over 15 000 years ago, Prehistoric hunters carved horses, bison and reindeer, some of which are over two meters long, straight into the Limestone cliffs. Cap Blanc, which was discovered in 1909, is today the only frieze of prehistoric sculptures in the world to be shown to the public.

All around this monumental frieze, a museographical area provides the visitor with an overview of Cap Blanc life and art. Objects, pictures, and a fresco tell the story of Prehistoric sculptors throughout Europe.

The limestone rock shelter of Cap Blanc, near Laussel, northeast of Les Eyzies in France’s Dordogne region, is well known to the world of prehistory as the site of one of the finest sculptured friezes to survive the last Ice Age, the first to be unearthed, and currently the best to remain open to the public. Its figures of horses, bison and deer, albeit found in a much damaged condition at the time of their discovery by Dr. Gaston La lanne of Bordeaux in 1909, remain a moving and powerful ensemble. La lanne dug here and unearthed a fine collection of typical Magdalenian – about 15 000 years old – stone, bone and antler tools, including harpoons, and a number of large stone implements that had clearly been used to produce the parietal bas-relief and haut-relief sculptures that his crude excavations brought to light on the back wall. (Ed: Parietal – term used to describe artwork done on cave walls or large blocks of stone, as opposed to portable art, such as most of the venuses)

In 1911, further digging in front of the shelter for the purpose of erecting a small construction to enclose and protect the frieze and for lowering the floor level to make the art more visible to visitors led to the discovery of a human skull. Work was suspended and prehistorians Louis Capitan and Denis Peyrony were asked to extract the skeleton, a task that took them three days.

The Cap Blanc skeleton is of tremendous importance – not only a relatively intact inhumation from the late Ice Age but also one of the very few found in close proximity to parietal art of the period.

Indeed, the body’s location directly in front of the central part of the shelter’s sculptured frieze can really only be compared with that of the double paleolithic inhumation of an adult woman buried with her arm around a 17-year-old male dwarf in front of the engraved block at the Riparo di Romito, Italy. It was suggested by the excavators that the Cap Blanc burial may even be that of the original sculptor (or one of them), and this is unquestionably a possibility; certainly the location of the inhumation indicates a person with a strong link to the site.

Conflicting Reports

In France, the excavation of the skeleton in 1911 led to a brief publication that discussed primarily the two skeletons unearthed at La Ferrassie by the same excavators. They gave few details about the Cap Blanc find, stating only that the skeleton lay at the bottom of the archaeological deposit, 2. 3 meters from the frieze and 60 centimeters below the hooves of the central horse. It had been buried amid stones, with three fairly big stones placed above it, one of them on its head and others at its feet. It had been placed on its left side, arms and legs flexed, occupying a space of only 3 feet by 2 feet (1 meter by 60 centimeters), immediately below a Magdalenian hearth.

It is curious that early reports of the Cap Blanc skeleton claimed that it was of a male aged about 25, whereas examination by physical anthropologists eventually established that it was of a young adult female.

A recent examination of the field Museum’s archive on the case made it possible to reconstruct much of the story. The earliest document in the archive is a letter, dated January 24, 1911, to Monsieur J. Grimaud, the site’s owner, from the president of the Société des Antiquaires de 1′Ouest in Poitiers, acknowledging receipt of a report on the rock shelters of Laussel (i.e. Cap Blanc) together with photos and five boxes, one containing reindeer teeth and bones and the other four containing flint tools. A letter, dated August 5, 1911, from Paul Leon, at the Ministère de l’Instruction Publique et des Beaux-Arts in Paris, thanks M. Grimaud for reporting the discovery of the skeleton and states that he will ask Peyrony to take appropriate measures to preserve it. Peyrony himself (the Membre Correspondant de la Commission des Monuments Historiques aux Eyzies) writes on August 8 that the Minister has asked him to verify the authenticity of the Laussel skeleton, make all necessary scientific observations, and supervise the excavation. He therefore went to the site that very morning and examined the find in the presence of Grimaud’s guard, Veyret. The remains were indeed authentic.

Only two days later, Grimaud received a letter from Dr. Capitan, professor at the Collège de France, dated August 10, which is a key document for the site. The letter contains a sketch of the location of the bones and reports that they are 2. 3 metres from the big horse and around 70 centimetres below its muzzle. They occupy a kind of pit, 50 centimetres deep, and the skull was unfortunately broken by a blow from a workman’s pickaxe.

Capitan insists, rightly, that the excavation be carried out by experienced and qualified people and suggests himself and Peyrony for the task, as they have just unearthed the two older skeletons from La Ferrassie. To make matters clear, he proposes that the excavators produce the scientific report, while any finds would belong to Grimaud. In the meantime, the skeleton has been covered with stones and planks for its protection.

A new letter from Capitan, dated August 28, reports that the skeleton has been removed in its entirety in a number of blocks of earth, and it will now be possible to excavate the bones properly and carefully, once Peyrony has transported them to Paris by rail, probably in September or October. For the present, these blocks are in Peyrony’s care, and he will dry them out slowly. Most important is a brief sentence, stating that “All we found with the skeleton was a shapeless fragment. probably of ivory.” This is indeed a small ivory point measuring 0. 6 by 3 by 0. 4inches (16 by 74 by 10 millimetres), which is kept at the Field Museum, having been sold along with the skeleton.

It is described as “several thin laminae glued together along with bits of matrix and partially reconstructed or plastered over with some sort of filling material.” According to its original display case label, this point was “found over the abdominal cavity of this individual” and “the weapon may have been the cause of death. ”

This is certainly the theory that was promoted by Henry Field, the eventual acquirer of the skeleton for the museum. He claimed in a 1927 article that the skeleton died a natural death, yet also noted: A small ivory harpoon-point found lying just above the abdomen may give a possible clue to the cause of his death. This weapon may have caused blood poisoning which resulted in death. It has been suggested tentatively that the young man [sic] felt death approaching and returned to the rock-shelter, as he desired to die before the masterpiece he had helped to create. . . It is not plausible that some one who had nothing to do with the sculpture should have been allowed to desecrate the sanctuary unless he had assisted in the work or, at any rate, was directly connected with it.

In Field’s memoirs, his speculations were even more romantic: “Why had she been buried beneath the frieze of horses? Was she killed by her lover’s ivory lance point? Was it by another Cro-Magnon girl? Was her brother avenging the family’s honor? Was she killed in battle? Why was she buried in the sanctuary? Was she the daughter of the sculptor-high priest? There was no real evidence, except that death probably resulted from blood poisoning.”

No source is given for the theory that the ivory point was the cause of death or the claim that it was found above the abdomen – perhaps this was merely M. Grimaud’s opinion – but nevertheless it is baffling that such a potentially important object was completely omitted from the published report by Capitan and Peyrony. Indeed, were it not for this casual mention in Capitan’s letter, there would be absolutely no guarantee THE CAP BLANC LADY that the point had any connection with the Cap Blanc skeleton. Yet ivory is not common in Magdalenian contexts in southwest France, let alone ivory points that may be a cause of death. In this connection, it is worth noting that the only clear evidence we have of violence inflicted on humans during the last Ice Age consists of a probable flint arrowhead embedded in the pelvis of an adult woman from San Teodoro Cave, Sicily, and an arrowhead in the vertebra of a child from the Grotte des Enfants at Balzi Rossi, Italy.

A letter to Grimaud from Peyrony, dated August 31, 1911, notes that”we have been able to lift the whole thing in a pretty good state. The whole skeleton will be able to be reconstructed and will be a very good study piece. I have conserved it in Les Eyzies, as Mr Capitan was not able to take it. I will carry it to Paris next October. ” However, it is clear that Capitan had major problems in getting the skeleton dealt with in Paris. Letters from him complain of the difficulty in finding someone qualified and with sufficient time available to prepare the bones for casting and display. It is also interesting to learn that there were plans afoot to have a cast made and placed in the shelter; in fact, for some reason this was never done, and instead a miscellaneous collection of casts of other bones was put together for this purpose. In a letter dated July 29, 1913, Capitan tells Grimaud that an artist will be sent to carry out this assignment. A letter from Grimaud in 1924 notes that “in accordance with the Ministere des Beaux Arts, I have had a modern skeleton set in place at the foot of the sculptures, in place of the real skeleton. ”

Nevertheless, the original skeleton was eventually extracted from its sediments by J. Papoint of the Laboratoire de Paleontologie at the Musee National d’Histoire Naturelle under the direction of Marcellin Boule(director of the museum) and of Capitan. A letter from Papoint, dated February 27, 1915, records the state of the bones:

You will find the skull in the wooden box. It is in two pieces. It was impossible for me to reconstruct it because of the deformation caused by fossilisation. I left in the same block the upper and lower jaws as well as the seven cervical vertebrae which I extracted as well as I could. There are two upper incisors that I put to one side, since I could not fit them in their sockets. These two skull pieces are very fragile and need to be unpacked with care. The dorsal and lumbar vertebrae are all present. The ribs are incomplete. All the limb bones are in good condition. A few fragments of the shoulder-blades and pelvis bones are missing. This is due to the fragility of certain parts of these bones. A few phalanges are missing from the hands and feet. The Sale of the Bones By early 1915, the Cap Blanc skeleton had been restored to its owner. Monsieur Grimaud. It then disappeared from view until the start of his attempt to sell it to an American museum nine years later. According to Henry Field, “in 1916 M. Grimaud, having made no money out of the discoveries on his property, decided to reclaim his anticipated profit, and during the stress of war conditions was able to ship the skeleton to New York.” In his later memoirs, he added that “the skeleton was said to have been smuggled out of France during World War I in a coffin as an American soldier with the necessary papers forged.” Yet documentation available at the Field Museum provides no real clue as to why Grimaud decided to send it to America, or why he apparently waited a further eight years before trying to sell it. His initial choice was the American Museum of Natural History in New York, but, to cut a long story short, his protracted negotiations, via American lawyers in Paris, eventually came to nothing, in part because of his huge asking price ($12, 000, equivalent to about $250, 000today).

Finally, after steadily dropping his price, he sold it to Chicago’s Field Museum for a much lower amount. According to Field’s memoirs, a representative of the museum was sent to Monsieur Grimaud “with twenty-five thousand-franc bills (the equivalent of a thousand dollars) in one hand and a receipt ready for signature in the other. ” He continues, “Some days later a cable came from Paris saying that the Cap-Blanc skeleton was ours. I hurried to New York and in the basement of the Museum of Natural History packed her very carefully in cotton wool and carried her in a suitcase to a compartment on the Twentieth Century [train]. We had a very uneventful night together. ”

With the benefit of hindsight, Field’s memoirs claim that, as he laid out the bones in Chicago, “the pelvic girdle was definitely feminine” – yet, as noted above, his article of 1927 still saw the skeleton as a young man! The skeleton in its new case was first displayed prominently just inside the museum’s main entrance.

It was introduced to the media as “the only prehistoric skeleton in the United States”, and so became front-page news. The first day, 22 000 visitors came to see for themselves. At noon, the crowd was so dense around her that the captain of the guard. . . notified the director that two guards must be placed there to keep the people moving and orderly. . . . Nothing like this had happened before in the Field Museum. . . . This was the first exhibit in the new building to capture the public and press imagination. ”

In 1932, the skeleton was withdrawn from exhibition so that the skull could be restored by T. Ito under the direction of Gerhardt von Bonin of the Department of Anatomy at the University of Illinois. According to von Bonin:

When the skeleton arrived at the Museum, it was in an almost perfectly clean condition, only a few bones being still embedded in a matrix of somewhat gritty, loam-like matter. The long bones were almost all perfectly preserved. The pelvic and the shoulder girdle were somewhat damaged, particularly in the pubic region and the scapula. The vertebral column appeared to be complete, the vertebrae were for the most part still held together by adhering soil. Twelve left and ten right ribs were found, and a rather decayed square piece of bone, apparently all that was left from the manubrium sterni. The cervical column was firmly attached to the lower jaw and a part of the upper jaw.

The skull was broken into a number of fragments. The bones are of a brownish colour, darker in some spots and lighter in others. They are firm enough to be handled conveniently, yet somewhat brittle. In some spots, dental cement had been put on the bones in order to prevent them from crumbling.

Von Bonin’s conclusion, after a full anatomical study, was that these were the remains of a young woman, about 5 feet, 1 inch (156 centimeters) tall and about 20 years of age.

In an exhibition case next to the skeleton, the museum installed a life-size diorama of the Cap Blanc rock shelter, modeled by Frederick Blaschke. As the only complete European paleolithic skeleton on exhibition in an American museum, the Cap Blanc woman was seen by several million visitors in her first decade in Chicago alone. But the story does have a happy ending of sorts.

Thanks to the generosity of a private sponsor, a complete cast of the Cap Blanc lady – and of her ivory point was made, and on July 14, 2001, the cast was installed in its rightful place beneath the central frieze in France.

Looking for accommodation in Les Eyzies?

B&B Ferme de Tayac, lovely 12th Century buildings, once monastery and farm. Its one meter thick walls, oak beam structures, and rooms carved out of the rock, make it a wonderful place to stay whilst you explore this fascinating part of the Vezere Valley. Your stay will be enhanced by the friendly hospitality and homely comfort offered by your hosts Suzanne and Mike. You will enjoy the pleasant garden, the refreshing swimming pool, and maybe the occasional five minute stroll into Les Eyzies, famous as the “Prehistoric Capital of the World” It is here that Cro Magnon man our ancestor made it one of the richest and most exciting of archaeological areas.

Ferme de Tayac is just a 10 min. drive to Cap Blanc – www.fermedetayac.com