Discovery

Discovery

The first remains now known to be Neanderthal were discovered in Belgium in 1829, and further remains were discovered in Gibraltar in 1848. However, it was the 1856 discovery of a partial skull and an assortment of arm, leg and rib bones in the Neander Valley that led to the recognition of Neanderthals as a separate species by Hermann Schaffhausen. ‘Tal’ is the word for ‘valley’ in modern German, having replaced the ‘Thal’ of the slightly dated 19th Century dialect, hence the confusion between Neandertal and Neanderthal. In the light of Darwin’s Origin of Species, published three years later in 1859, Neanderthals became the first bones to be recognised as a ‘missing link’ between humans and apes, of the type that Darwin predicted.

Appearance

Neanderthal and human remains can be difficult to distinguish, especially when dealing with very partial remains. Differences include an occipital bun (lump on the back of the head), lack of a chin, more prominent brow-ridge, broader nose, slightly bowed leg-bones and a generally more robust physique. Most of these features can be found in human skeletons to some degree; for instance, although humans have smaller skulls on average, it is not true to say that all humans have smaller skulls than all Neanderthals. We have no direct way of telling whether Hn had a variety of hair, eye or skin colours, or indeed how much hair they had.

Early Theories

Since Darwin’s theory of evolution was unpublished when the first Neanderthal bones were discovered, scientists struggled to work out what they were. They were clearly more similar to human bones than those of any other living creature, and yet they were at the same time clearly not those of ordinary men. One theory, proposed by Rudolph Virchow, was that they were the remains of a man (assumed to be from Napoleon’s army) who had suffered from a unique form of debilitating rickets as a child, gone on to become a horseman causing him further deformities, suffered a series of crippling head injuries and ended up dying naked in a German valley just miles from the nearest village.

When the first complete set of Neanderthal remains was found at La Chapelle-aux-Saints in France, Pierre Marcellin Boule reconstructed the individual in what would become the classic image of Neanderthals, stoop-backed, bent-kneed and with a ‘dumb’ brow and jaw. Later revisions would show that this individual had suffered from severe arthritis of the spine, but probably had little stoop if any.

‘Out of Africa’ v ‘Multi-region Hypothesis’

From the late 19th Century onwards, it was believed that modern humans were the result of a mixture of genetic traits, developed in separate parts of the world in mutually interbreeding populations. During the 1980s and 1990s, this theory was displaced by the single origin or ‘Out of Africa’ model, which envisaged several species of human evolving in Africa and migrating outwards into Asia and Europe, with each wave of migration displacing the previous one. This was based initially on finds of anatomically modern humans living in Africa 200,000 years ago, backed up by analysis of the mitochondrial DNA of Neanderthals and sapiens, showing that they diverged roughly 500,000 years ago.

More recently, a compromise between these two models appears to have been reached. Although the ‘Out of Africa’ scenario is still held to be generally correct, there is now increasing genetic evidence that inter-breeding did occur between sapiens and Neanderthals, and possibly between sapiens and erectus1 as well. However, gene flow appears to have been very limited, so we seem to be looking at distinct but occasionally interbreeding groups, rather than a homogenised group. Individual hybrids must have been completely incorporated into the society of either sub-species.

More detail can be found in the ‘Science Bit’ below.

How Similar Were They To Humans?

How Similar Were They To Humans?

Neanderthals were, until around 24,000 years ago when they disappeared, the closest known relatives to modern humans2. We now have partial remains of over 400 Neanderthal individuals, making them the best-studied and most recent of the relatives of modern man. None of these bones have been fossilised, and some are intact enough to have had fragments of DNA extracted. Perhaps because they were first known as ‘missing links’, they have always been portrayed in the mass media as midpoint between humans and apes, with a stooped posture, receding brow and no culture except, perhaps, a few strategically placed pieces of animal hide.

This has, however, long been at odds with scientific interpretation both of Neanderthal remains and of the artefacts associated with them. Although Neanderthals are not now widely considered to be directly ancestral to Homo sapiens (with both species instead being descended from other Homo species), they remain far more closely related to us than most of the other extinct hominins3.

Neanderthals had notably large brains – larger on average than Homo sapiens. The average modern human has a brain capacity of around 1400cc. Neanderthals actually had larger brains, at 1500cc, which may seem surprising except for the facts that brain size does not indicate intelligence (whales, anyone?), and Neanderthal brain volume to body mass ratio is actually lower than in sapiens. They would have walked with a fully upright posture, and were capable of making tools of equal quality to those of Homo sapiens. The oldest known musical instrument is a fragment of a bone flute found at a site associated with Neanderthals, so they may have been the world’s first musicians (not including the whales, of course).

Neanderthals are believed to have contributed genetic material to modern humans by interbreeding with early Homo sapiens. This means that they were of the same species as humans; and since the evidence is that this interbreeding continued until the disappearance of Neanderthals, it seems that Neanderthals were never reproductively isolated from humans.

First Appearance

Neanderthals lived in many varied locations, and over a great length of time. It is not surprising that they varied in appearance, with those from more southerly regions being less adapted to the cold than their more northerly cousins.

Many of the traits that distinguish Neanderthals from sapiens and erectus are related to temperature. Neanderthals lived in Europe during a cold period in the Earth’s history – an ‘ice age’ – and consequently had adaptations including a broader nose (more efficient at heating inhaled air) and a squat, compact frame that minimised surface area to volume ratio and so reduced heat loss. The defining image of Neanderthals in popular culture – their stupidity – is categorically incorrect. Neanderthals had a sophisticated culture, and made some developments before their sapiens cousins.

Some cold-adapted traits first appeared in European hominins as long as 1,000,000 years ago in Iberia. However, this does not necessarily indicate genetic separation of the African and Neanderthal strains, which from genetic data is supposed to have happened closer to 500,000 years ago.

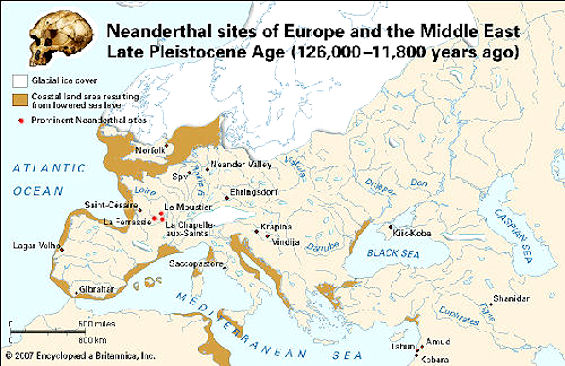

At its greatest extent, the Hn subspecies occupied all of mainland Europe south of Denmark and Scandinavia, the southern UK (the Watford Gap is old indeed), and roughly what is now Turkey, Iran, Syria, Iraq and even Uzbekistan.

Culture

The culture of Neanderthals is technically known as Mousterian, after Le Moustier in France, where a Neanderthal skull was found. This refers largely to the design of stone scrapers, probably used for either scraping skins or simple woodwork. There is no evidence that Neanderthals ever developed the ability to sew, so it is unlikely that they wore clothing (despite the cold climate). It seems that Neanderthals made use of fire, but probably not for warmth. They do not seem to have constructed any structures, even tents. Mousterian technology includes stabbing spearheads and axes, but no throwing spears or arrowheads.

Animal remains are frequently associated with Neanderthal sites, indicating that they were meat-eaters. Interestingly, these remains are usually of animals in their prime, something usually associated with farming rather than hunting (where elderly or infirm animals would be easier to catch). Injuries found in Neanderthal skeletons are frequently similar to those found in rodeo clowns, which implies that Neanderthals often wrestled with large animals. This most likely indicates a close-quarters hunting method, although it is possible that livestock was also kept. Many of these injuries (for instance those suffered by the aged individual recovered at La Chapelle-aux-Saints in France) would have been debilitating, which indicates a communal structure that tended to the infirm.

Whistles made from the phalange bone of a reindeer leg – what would be a finger or toe bone in humans – are known from 90-100,000 years ago, but it is unclear whether these were used for music; an artefact that may or may not be a flute is known to have come from 20,000 years later, although many maintain it is a bone with bear tooth-holes in it. Neanderthals buried their dead, and one burial at Shanidar in Iraq was accompanied by grave goods in the form of plants. All of the plants are used in recent times for medicinal purposes, and it seems likely that the Neanderthals also used them in this way and buried them with their dead for the same reason. Grave goods are an archaeological marker of belief in an afterlife, so Neanderthals may well have had some form of religious belief.

Some Neanderthal burials appear to show incisions on the bones that would indicate butchery. This may be evidence of cannibalism, either by Neanderthals or sapiens. Whether this was an act of desperation or a religious ritual is not known, but it is generally accepted. However, it must be seen in the light of the other, more careful Neanderthal burials that would indicate a general respect for the dead.

Extinction

Neanderthals were adapted for a colder climate than their African cousins. Temperatures in Europe have fluctuated greatly over the past half-million years, with glaciers covering Scandinavia for long periods. It was long believed that rising temperatures, in combination with competition from sapiens, led to the disappearance of Neanderthals.

More accurate measurements of palaeoclimate have altered this view. The temperature increased from around 24,000 years ago, reaching its highest levels for 130,000 years. Neanderthals had survived at least two such warm spells (interglacial periods) before, and this third warming appears after final decline.

Neanderthals shared Europe with Homo sapiens for several tens of millennia, during which Hn appear to have been in decline. It is unclear whether there was direct competition between the two species; it seems more likely that competition was indirect, with H. sapiens being better at running after prey and using hurling weapons, and H. neanderthalensis no longer having the advantage of its cold-weather adaptations. It is also possible that rapid changes in climate denuded the forests; without sufficient cover to sneak up on their prey, the Neanderthals slowly found their ambush-hunting methods becoming ineffective – contrast this with the sapiens, who were able to use ranged weapons and relied less on the cover of the forests to hunt. However, this idea would clash with the evidence that the Neanderthals farmed animals.

There is some evidence that the range of Neanderthal dwellings tailed the ice northwards, with Homo sapiens colonising Europe from the south. However, this is inconclusive; Neanderthals survived at the extremities of Europe, with the last known population being in Gibraltar (ironically, at the southern limit of their range).

The Science Bit

The ‘Multiregion Hypothesis’ was first proposed in 1964, dominated throughout the 1980s, then fell out of favour during the 1990s. Mitochondrial DNA analyses of modern humans show that the most recent female ancestor common to all living humans lived less than 170,000 years ago – long after we diverged from Neanderthals 500,000 years ago. Later Y-chromosome analyses showed that our most recent male ancestor is around 100,000 years old. Although this was good evidence, it could also be explained by all part-Neanderthal lineages passing through an all-male generation, so that no Neanderthal mtDNA was passed on. Recovery in 1987 of mitochondrial DNA from a Neanderthal bone offered further confirmation of this theory.

The discovery in 1999 of a 24,000-year-old adolescent skeleton in Lapedo, Portugal (the Lapedo Child) with an apparent mixture of Neanderthal and sapiens characteristics has led to speculation that rather than going extinct, Neanderthals may have interbred with modern-type humans. More recently, a second alleged hybrid has been unearthed in Romania, and this idea has been backed up by more detailed genetic analyses. Haplotypes are sections of DNA that do not appear to be reshuffled during sexual reproduction. Although the majority of human haplotypes are consistent with ’shallow ancestry’ – the idea that Homo sapiens evolved in Asia around 160,000 years ago – a small number seem to show deeper ancestry. A haplotype known as PDHA1 seems to have diverged around 1,800,000 years ago. It is difficult to explain how both varieties survived if humans were reduced to a small population (a bottleneck) much later than that; this gives support to the idea that it was introduced into the population by interbreeding with another population, such as Neanderthals. This re-introduction of genetic material is known as introgression.

Another example is the haplotype microcephalin, which diverged around 1,000,000 years ago but seems to have introgressed around 40,000 years ago. This ties in very neatly with the fossil dates for the appearance of Neanderthals and their simultaneous occupation of Europe with Homo sapiens. Both these examples are of genes that appear to offer an advantage, and have spread throughout the population by natural selection. This makes it impossible to tell whether they were introduced multiple times or just once, so they cannot be used to judge the frequency of Neanderthal/sapiens hybrids. The next step in research is to analyse ‘junk’ haplotypes, which cannot be selected for or against and are thus unaffected by natural selection. If these are found to be common, it would indicate frequent hybridisation events.

Finally, the RRM2P4 haplotype appears to have diverged 2,000,000 years ago. This pre-dates the separation of sapiens and Neanderthals, so it offers a hint that our ancestors may have bred with another sub-species, Homo erectus.

Any two groups that interbreed in the wild are defined as the same species, so Neanderthals are now recognised as a sub-species of humans, and are officially known as Homo sapiens neanderthalensis, as opposed to Homo sapiens sapiens, which covers everything from Cro-Magnon man to ourselves.

Controversies

As if the debates described above were not enough, there are a number of theories somewhere on the spectrum from the radical to the ridiculous. Below are some examples of ideas that are not generally accepted by palaeontologists but that do occasionally circulate.

Some studies indicate that Neanderthals may have had considerably longer lifespans than humans. This is not widely accepted, as it is based upon the assumption that rates of maturation in Neanderthals are very similar to those in Homo sapiens. Specifically, ages are calculated according to tooth wear and this is then correlated to maturity of the specimen in terms of height, development, etc. The conclusion is that Neanderthals took longer than sapiens to reach maturity, and thus that their lifespan must have been correspondingly longer. Almost every stage of this line of argument is contentious, and it is highly notable that no Neanderthal remains of individuals with an apparent age greater than around 40 years have been found.

Creationists, naturally, contend that Neanderthals are fully modern humans, often arguing along the lines of Virchow’s discredited theory that the differences between Neanderthals and sapiens are caused by injuries and pathologies. The sheer quantity of Neanderthal remains now known make it difficult to conceive of all individuals suffering the same injuries, and means that palaeontologists universally reject this idea.

Finally, it has been proposed that the related group of neurological disorders that include autism, Asperger’s syndrome, dyslexia and attention deficit hyperactive disorder (ADHD) may be due to the presence of Neanderthal genetic material, rather than mis-functioning genes. Supporters of this theory draw parallels between the symptoms of autism and deduced behaviours of Neanderthals: dispraxia (lack of hand-eye coordination) compared to absence of Neanderthal throwing weapons; seasonal affected disorder (SAD) may indicate Neanderthals hibernated; autistic children typically have a slightly larger brain; and difficulty in learning a language. They also note that autism is more common among people of European descent, who would be expected to have more Neanderthal genes than those of purely African or Asian descent. Opponents point to the circumstantial nature of this evidence, maintain that there are many symptoms of autism that are not explained in this way, and object to the assumptions made (there is no direct evidence to support the idea that Neanderthals hibernated outside of the Neanderthal theory of autism, and Neanderthals may well have had a language).

——————————————————————————–

1 Homo erectus was another relative of both Homo neanderthalensis and Homo sapiens.

2 With the possible exception of the disputed taxon Homo floriensis, known to the popular media as ‘hobbits’.

3 ‘Hominin’ is the term used for all humans, living and extinct. ‘Hominid’, formerly used for humans, has now been widened to include apes. It is now possible that Neanderthals may have been driven extinct by terminal confusion about their own identity.